Silas Aaron Hardoon was born into a poor Jewish family in Baghdad in 1851, but when he died in Shanghai China 80 years later, he was regarded as the wealthiest man in Asia, leaving behind a fortune worth as much as $15 billion in today’s dollars.

Silas Aaron Hardoon was born into a poor Jewish family in Baghdad in 1851, but when he died in Shanghai China 80 years later, he was regarded as the wealthiest man in Asia, leaving behind a fortune worth as much as $15 billion in today’s dollars.

When Hardoon arrived in Shanghai as a youth of 17, he started working as a rent collector for the large commercial firm, David Sassoon & Company. With a keen eye for real estate, he began investing and making money as he quickly rose up the corporate ranks.

He was part of the first wave of Jewish immigrants to Shanghai, which included a significant number of Mizrachi (Eastern) Jews from Iraq who worked for big Jewish mercantile firms. Hardoon is credited with building Shanghai’s original Nanking Road, an opulent boulevard that is the equivalent of New York’s Fifth Avenue.

A noted philanthropist, he also built the grandiose Beth Aharon Synagogue in 1927 as a gift for the city’s Jewish community. In the late 1930s it became a haven for rabbis and students of the Mir Yeshiva as Shanghai became a refuge for Jews fleeing Nazi persecution in Europe.

Hardoon was 35 years old when he took a wife, Jialing Luo (“Liza”), a Chinese-born Buddhist who never converted to Judaism.

The couple were evidently married civilly at the British consulate in Shanghai, but because Hardoon was not yet a British citizen, the marriage was later considered to be null and void. No valid record of a Jewish marriage was ever found, details that would emerge after Hardoon’s death in 1931 and his will was contested in court, prompting a protracted legal battle that the international press followed avidly.

The couple were evidently married civilly at the British consulate in Shanghai, but because Hardoon was not yet a British citizen, the marriage was later considered to be null and void. No valid record of a Jewish marriage was ever found, details that would emerge after Hardoon’s death in 1931 and his will was contested in court, prompting a protracted legal battle that the international press followed avidly.

A certificate was produced after Hardoon’s death showing that he had been married according to the Jewish rites in a British civil ceremony, but the marriage was deemed of questionable legality both under the Jewish faith and according to the Foreign Marriages Act.

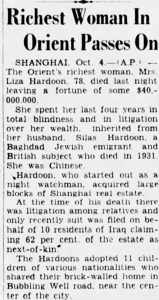

The Hardoons didn’t have any biological children. Instead they adopted about 10 or 11 children, all of whom were excluded from the will. When the courts determined that Hardoon’s wife should inherit his vast fortune because she had attended synagogue during one brief period and so could be defined as Jewish, the Jewish community and many of Hardoon’s cousins launched a court challenge.

One of Hardoon’s cousins beseeched a leading rabbi to write to the presiding judge and the local press so that “the public may not be misled that one who is deeply immersed in paganism can ever come under the ambit of the Jewish religion without conversion ceremony and be recognized as such.”

Isaac Silas Jacob Hardoon, a first cousin in Bombay, appealed to the court to be recognized as the deceased’s legal heir. A group of more distant cousins, under Ezra Abdullah Hardoon, also put forth a claim.

The Iraqi government also declared a strong interest in the estate. “Iraq government claims that the late Silas Hardoon at time of death was an Iraquian national under article 8-B, Iraquian National Law, and requests rights of Iraquian relatives may be safeguarded. Their claim is that the Iraquian law of succession should apply.”

The Iraqi government also declared a strong interest in the estate. “Iraq government claims that the late Silas Hardoon at time of death was an Iraquian national under article 8-B, Iraquian National Law, and requests rights of Iraquian relatives may be safeguarded. Their claim is that the Iraquian law of succession should apply.”

Iraq was once a province of the Turkish Ottoman Empire, which dissolved in 1918, its lands subsequent falling under British protection. Originally a Turkish subject, Hardoon had applied for both British and French consular protection, but it was determined that neither of these conferred upon him British or French citizenship.

These were among the myriad considerations of this convoluted case that twisted its way through the British Supreme Court for years. Hardoon’s aging widow eventually inherited his wealth but she died in 1941 and the Chinese communists ultimately nationalized the Hardoon fortune after their takeover of Shanghai in 1949.

Although little is known of the fate of the adopted children, one of the adoptees (born 1926) eventually settled in Toronto, where he raised a family and died in 2012. ♦

From Canadian Jewish News, 2018

See also: Shanghai’s Baghdadi Jews (book review)