Seeking to extend their colonial holdings in the early 1800s, the major European powers considered the notion of dispatching expeditions through the forbidden Sahara Desert to Timbuktu, the legendary lost city of gold in the heart of Africa.

Seeking to extend their colonial holdings in the early 1800s, the major European powers considered the notion of dispatching expeditions through the forbidden Sahara Desert to Timbuktu, the legendary lost city of gold in the heart of Africa.

Rumors of the vast wealth of Timbuktu had been circulating ever since 1324, when Mansa Musa (“Emperor Moses”) had made his sensational appearance in Cairo. Potentate of a fabulously wealthy desert kingdom, Mansa Musa was a devout Muslim from Timbuktu who was enroute to the Arabian cities of Mecca and Medina on a haj or holy pilgrimage. According to legend, he led a great caravan across the desert with an entourage of as many as 60,000 followers, some 500 slaves each bearing a staff of solid gold, and 100 camels laden with sacks of gold dust. His arrival in Cairo significantly depressed the price of gold for many years.

Born in Morocco, Rabbi Mordochai Abi Serour was the first non-Muslim to settle in the fabled African city, and one of few travellers to write about the Jewish “Daggatouns” of the Sahara Desert

By the early 1800s scores of European explorers had set off for the fabled city, and if any had ever reached it, none had returned: the journey was extremely arduous, the terrain bleak and unforgiving, the sands littered with skeletons. In 1805, for instance, a convoy of 2,000 men and nearly as many camels died of thirst enroute from Marrakesh. Hostile desert tribes posed an additional menace, since marauding bands of robbers routinely slaughtered non-Muslim travellers.

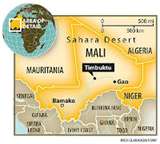

Disguised as a Muslim, the French explorer Rene Caillie set off from the coastal city of Freetown in 1828 and reached Timbuktu after an intensely difficult journey of several months. His impressions of the once-thriving outpost were disappointing. Even from a distance he could see it was no great metropolis of wealth and grandeur but “a mass of ill-looking houses built of earth” and surrounded by “immense plains of quicksand of a yellowish-white color.” In 1853 the German explorer Dr. Heinrich Barth became the second known European to return from Timbuktu. He described a city situated on a bend in the Niger River in the western Sudan, with a population of roughly 6,000 to 10,000, and deprived of all except the most rudimentary resources of life.

Disguised as a Muslim, the French explorer Rene Caillie set off from the coastal city of Freetown in 1828 and reached Timbuktu after an intensely difficult journey of several months. His impressions of the once-thriving outpost were disappointing. Even from a distance he could see it was no great metropolis of wealth and grandeur but “a mass of ill-looking houses built of earth” and surrounded by “immense plains of quicksand of a yellowish-white color.” In 1853 the German explorer Dr. Heinrich Barth became the second known European to return from Timbuktu. He described a city situated on a bend in the Niger River in the western Sudan, with a population of roughly 6,000 to 10,000, and deprived of all except the most rudimentary resources of life.

The third non-Muslim to reach Timbuktu and the first to reside there for an extended period was the Jewish adventurer Mordochai Abi Serour. A rabbi, adventurer, merchant and guide from Morocco, Abi Serour first set out from Akka in 1858 along a traditional trade route for Muslim caravans. Travelling openly as Jews, he and his brother Isaac joined a bejaouis or small caravan that took six days to reach the Moroccan trading village of Tindouf, 20 days to the region of Erg Yguidy and 10 days to the oasis of Telyg. Passing the salt mines of Taoudenni, they continued through the desolate landscape to Ounan and Araouane. “There one enters fully into desert,” Abi Serour wrote, “where nothing has life, where nature is completely dead; an immense plain like the ocean, of which no one knows the width, and whose length is a week’s journey.”

The third non-Muslim to reach Timbuktu and the first to reside there for an extended period was the Jewish adventurer Mordochai Abi Serour. A rabbi, adventurer, merchant and guide from Morocco, Abi Serour first set out from Akka in 1858 along a traditional trade route for Muslim caravans. Travelling openly as Jews, he and his brother Isaac joined a bejaouis or small caravan that took six days to reach the Moroccan trading village of Tindouf, 20 days to the region of Erg Yguidy and 10 days to the oasis of Telyg. Passing the salt mines of Taoudenni, they continued through the desolate landscape to Ounan and Araouane. “There one enters fully into desert,” Abi Serour wrote, “where nothing has life, where nature is completely dead; an immense plain like the ocean, of which no one knows the width, and whose length is a week’s journey.”

Near Araouane, the caravan encountered hostile tribesmen who threatened to slay the two Jews; luckily, Abi Serour’s encyclopedic knowledge of Islamic customs impressed their captors, who ultimately accepted a “tribute” of half of their possessions in exchange for their lives, in accordance with Shari’a or Muslim law. After a lengthy wait in Araoune, Abi Serour joined another caravan that would carry him the 150 miles to his destination. Necessarily disguised as a Muslim, he reached Timbuktu in 1859, whereupon he foolishly dropped the disguise and set up shop as a merchant. A posse of Arab merchants, unwilling to permit a Jew to break their commercial trading monopoly, offered him a generous ultimatum: leave town at once, convert to Islam, or be killed. Again drawing on his knowledge of Shari’a, Abi Serour argued his own case before the Emir and the Sultan, impressing them both. By agreeing to pay an annual tribute of half of his possessions, he was permitted to stay.

In 1860 Abi Serour’s brother joined him, and three years later the pair returned to Morocco with a small fortune. After making a quick trip to Genoa and Venice to buy glass beads, which were much prized in Africa, Abi Serour and several family members and friends departed for Timbuktu in 1864. They were plundered enroute but luckily reached Timbuktu safely, bringing with them 11 Jewish men, enough to form a minyan (a religious quorum).

In 1869 Abi Serour and three companions left Timbuktu for Akka with two gourds of gold dust. Encountering a troupe of marauding Rguibet tribesmen, they quickly buried their gold and donned Arab clothing. Upon being forced to strip, they were found out and the gold discovered; they would have been murdered had not Mordochai attained protection from five Shgarna tribesmen travelling with the Rguibet. After a violent confrontation, Abi Serour and his one surviving companion were forced to travel naked with the band for a week, covering 30 miles per day and subsisting on small amounts of food and drink.

Despite the extreme hazards, Abi Serour returned to Timbuktu several times more. At the insistence of the French explorer August Beaumier, the Moroccan rabbi was sent to Paris to learn basic skills in geography, geology and botany: he was not an apt pupil and was considered uncouth. Still, he was hired to gather plant specimens in the Pay Sous region of Morocco, and found several that were new to science.

Despite the extreme hazards, Abi Serour returned to Timbuktu several times more. At the insistence of the French explorer August Beaumier, the Moroccan rabbi was sent to Paris to learn basic skills in geography, geology and botany: he was not an apt pupil and was considered uncouth. Still, he was hired to gather plant specimens in the Pay Sous region of Morocco, and found several that were new to science.

In 1879 the Alliance Israelite Universelle in Paris asked Abi Serour for a written description of his adventures. His short Hebrew manuscript included a description of the Daggatouns, a group of white-skinned apostate Jews who were scattered throughout the Sahara (and who have since apparently vanished). As to their origin, he explained that they came from Tementit, one of four Moroccan towns (the others were Tafilet, Tebelbelt and El Hammada) in which Jews had lived prior to the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem. Tementit, wrote Abi Serour, “was formerly one of the capitals of Judaism, peopled with Jewish scholars and writers” and possessing large Jewish tombs more than 1,000 years old.

Abi Serour and his family lived in Mogadir in the late 1870s and moved to Algiers in 1880. There he met the French explorer Charles de Foucauld, whom he accompanied on his famous expeditions into remote areas along the Moroccan-Algerian border. It was to be Abi Serour’s last major adventure; after 15 months the two parted. In his memoirs De Foucauld paints an uncomplimentary picture of the half-blind rabbi as argumentative and difficult.

Rabbi Mordochai Abi Serour died in 1886 at the age of 55, and was buried at the cemetery of St. Eugene in Algiers. Much of our knowledge of him comes from secondary sources, unpublished letters and articles in obscure journals. The most thorough account of his adventures is contained in God’s Will: The Travels of Rabbi Mordochai Abi Serour, a 57-page study by Sanford Bederman, published by Georgia State University in 1980. ♦

© 2001, 2012