Devotion of Workers in Sweat Shops and Other East Side Hebrews to the Drama – The Productions of the Official Playwrights – Ways of the Yiddish Actors.

From The New York Sun, October 18, 1896

New York is the only city in the world where the Jewish stage has achieved anything like prosperity. While in Russia it is altogether proscribed by the Government, and in Austria and Roumania its patrons are not numerous enough, or prosperous enough, to support a single permanent theatre, this city has three large Yiddish play houses, all of which have enjoyed a fairly thriving existence of about ten years.

And yet even here the patronage of the Yiddish drama is limited to a small portion of the Jewish population. The American or German Hebrew, to whom Yiddish is a foreign tongue, never attends one of these theatres, and the Yiddish-speaking Russian, Galician, or Roumanian, who knows enough of the language of his adopted country to make out the plot of an English play, would consider it beneath his dignity as an Americanized immigrant to attend performances given in his crude native tongue. The pious old folks of the Ghetto deprecatingly shake their heads at every kind of playhouse as a place of ungodly or at least undecorous amusement.

But all this is made up by the devotion and ardor of the typical theatregoer of the Jewish quarter. There are thousands of enthusiastic playgoers I the Hester street region, and it would scarcely be an exaggeration to say that nothing short of serious illness or the lack of the price of a ticket could deter them from spending at least three evenings in the week in the Yiddish theatres. Most of them see each play over and over again and will not rest satisfied until they have nearly every word of it by heart and cam hum every tune of it to their sewing machines. This accounts for the rather picturesque scene, not infrequent in a Jewish play house, of the audience vying with the prompter in the performance of his duty or unrestrainedly joining the chorus.

Many a hard-working tailor spends all his spare pennies on the Jewish theatres. Nor will the genuine enthusiast content himself with paying for admittance to the performances, but he will occasionally club together with others of his kind to buy a costly present for some star. Nothing could better gratify the ambition of the votaries of the Yiddish drama than the condescension of some actor who consented to touch glasses or to have a coffee spree with them. As for the Jewish players, they are condescending enough in this direction and, as their worshippers are for the most part poor sweatshop workmen, the drain upon the exchequer of their admirers, which this honour involves, is sometimes felt keenly.

If you happen to be in the Jewish neighbourhood and come across an over-dressed, high-hatted, caped individual, stalking with a lordly gait and an expression to match on his clean-shaven face, with a shabby young fellow, beaming with obsequious delight, cringingly stepping by his side, you may safely set the couple down for a Jewish actor and one of his admirers. The high hat, by the way, hardly shelters a superabundance of intelligence, for the Yiddish players are, as a rule, recruited from the most ignorant classes of Russian or Roumanian Jews. Some of the prima donnas are even said to be unable to read their parts unaided. A good many of the Jewish actors owe their histrionic career to their connection, at an earlier period, with the choir of some synagogue; ability to assist in the services as a khazon, or cantor, having formerly been considered conclusive evidence of dramatic talent as well as of a capacity for mutilating an air from Verdi adopted to a situation borrowed from Dumas. This bit of history, by the way, sheds light upon another interesting fact, that for the Days of Awe (which include New Year and the day of Atonement), some of the leading Jewish actors have been known to desert the footlights for the pulpit. In such cases the growing of a temporary beard has been considered an adequate transformation to convert the player for ungodly amusement into a dignified “messenger of the people” to God. In justice to the orthodox Jewish community it must be added, however, that none of their regular congregations has as yet engaged an actor in the capacity of khazon, for the habit of shaving one’s beard – one of the worst sins known to orthodox Judaism – is enough to vitiate one as a holy vessel. Moreover, although a khazon is not expected to be up to the standard of piety exacted from a rabbi, the great majority of orthodox congregations require of him a much more sedate and God-fearing mode of life than is characteristic of the average Jewish actor.

Nevertheless the player who wishes to earn $100 or $1200 by officiating on the great holidays has no difficulty in obtaining employment in some of the temporary synagogues which spring up like mushrooms for the festivals. These short-lived congregations are for the most part formed by some of Israel who, attending no synagogue the rest of the year, have a sudden attack of religious fervor at the advent of the Ten Days of Penitence, which is the other designation of the Days of Awe. As performances on the three most important of these days are out of the question, the Jewish theatres are then rented for synagogues, and thus it sometimes happens, as was the case at the last Day of Atonement, that a temporarily bearded actor appears as a pleader before heaven for a congregation of sons of Israel between the very walls where he is accustomed to amuse them by comedy and dancing.

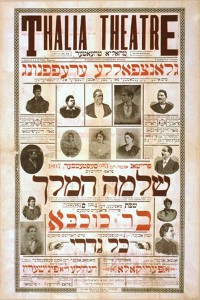

The three Jewish theatre, the Thalia, the Windsor, and the Liberty, all of which are situated on the Bowery near Canal Street, are all run by stock companies of actors, doing business on the cooperative plan, the number of shares allotted to each member being determined by his standing in the profession, or, to be more precise, by the volume and frequency of the applause he manages to evoke. A peculiar feature of these companies is the fact that each of them includes among its regular members an official author, whose duty it is to keep it supplied with plays. The name of this author appears beside the name of the manager on every bill of the company, even in case the play advertised bears the name of another writer. The aggregate constituency of all the three theatres being quite limited in number, a month’s run is considered a fair measure of success although some comic operas have enjoyed a much longer career. The official authors are thus constantly kept busy composing plays, and two of them, at least, have acquired the knack of turning out tragedies, comedies, and operas with a rapidity which, in point of prolificness, should secure to each of them the title of champion playwright of the world. It must be owned, however, that matters have been considerably facilitated for them by such gentlemen as William Shakespeare, Johann Schiller, and Victorien Sardou, each of whom may be laid under contribution, one for a piece of effective monologue, another for a spell-binding situation, still another for a bit of thrilling plot. But then, it takes time and labour to mistranslate and to generally mutilate the original, unwittingly or for the express purpose of disguising the plagiarism. In some cases the Yiddish dramatist will take a whole play bodily, confining his original work to changing the title and the names, including that of the author, for which he substitutes his own. There are nevertheless instances where the work is thoroughly original. Some of these original plays are suggested by a notorious current event. Thus a week or two after execution of Dr. Buchanan, the wife poisoner, a tragedy was produced at the Windsor Theatre, representing the murderer’s crime, trial, and last moments on earth. There are in the repertoire of the Yiddish stage a dozen or so plays which are advertised properly without sailing under false colours, and among these are “Hamlet,” “Othello” “Faust,” “The Gypsy Baron,” and “Blue Beard.”

The three Jewish theatre, the Thalia, the Windsor, and the Liberty, all of which are situated on the Bowery near Canal Street, are all run by stock companies of actors, doing business on the cooperative plan, the number of shares allotted to each member being determined by his standing in the profession, or, to be more precise, by the volume and frequency of the applause he manages to evoke. A peculiar feature of these companies is the fact that each of them includes among its regular members an official author, whose duty it is to keep it supplied with plays. The name of this author appears beside the name of the manager on every bill of the company, even in case the play advertised bears the name of another writer. The aggregate constituency of all the three theatres being quite limited in number, a month’s run is considered a fair measure of success although some comic operas have enjoyed a much longer career. The official authors are thus constantly kept busy composing plays, and two of them, at least, have acquired the knack of turning out tragedies, comedies, and operas with a rapidity which, in point of prolificness, should secure to each of them the title of champion playwright of the world. It must be owned, however, that matters have been considerably facilitated for them by such gentlemen as William Shakespeare, Johann Schiller, and Victorien Sardou, each of whom may be laid under contribution, one for a piece of effective monologue, another for a spell-binding situation, still another for a bit of thrilling plot. But then, it takes time and labour to mistranslate and to generally mutilate the original, unwittingly or for the express purpose of disguising the plagiarism. In some cases the Yiddish dramatist will take a whole play bodily, confining his original work to changing the title and the names, including that of the author, for which he substitutes his own. There are nevertheless instances where the work is thoroughly original. Some of these original plays are suggested by a notorious current event. Thus a week or two after execution of Dr. Buchanan, the wife poisoner, a tragedy was produced at the Windsor Theatre, representing the murderer’s crime, trial, and last moments on earth. There are in the repertoire of the Yiddish stage a dozen or so plays which are advertised properly without sailing under false colours, and among these are “Hamlet,” “Othello” “Faust,” “The Gypsy Baron,” and “Blue Beard.”

A Yiddish play, whether it is advertised as a drama or a tragedy, or a comedy, or “a great historical opera” – which last description seems to find particular favour with the Jewish authors and managers – mostly consists of a combination of all these species of stage literature and sometimes also of some exercises more akin to the acrobatic profession than to the stage into the bargain. To judge from the huge bills printed in Hebrew characters and displayed in all the grocery stores of the Seventh and Tenth wards, the Jewish players are classified into a rather large number of distinct categories, such as “wonderful tragedians,” “world-renowned tragedians,” “side-splitting comedians,” “universally beloved dramatists,” and “peerless character portrayers.” But as a matter of fact nearly every Jewish actor or actress combines in his or her own person the qualities of tragedian and comedian, and sometimes also the Yiddish equivalent of the dime museum lecturer: all of which talents he usually has occasion to call into use in the course of a single performance.

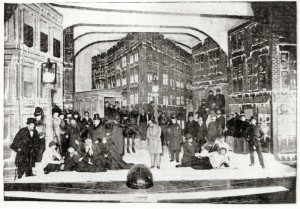

Very few Yiddish plays have any bearing upon Jewish life of today. “Historical operas,” with characters bearing Biblical names and with costumes of all periods and climes, form the staple commodity. These are preferred both because of the “Hebraic spirit” which they are supposed to contain, and also because of the opportunities they offer for spectacular effects, bombastic monologues, and terrific gesticulation. Indeed, what other source than the Bible would afford you the occasion of seeing on the stage a fair-sized whale, furnished with a glass window in its side to expose to view an old man praying within, as was the case a year ago when the Thalia Theatre produced the play called “Jonah the Prophet?”

The two or three really excellent operettas which are permeated with the genuine Hebraic flavor, in their librettos as well as in their music, belong to the pen of Mr. Goldfaden, the father of the Jewish theatre. His songs touch the tenderest chord in the Jewish heart; and they are sung often to the accompaniment of sighs and tears, wherever the Yiddish tongue is spoken. Mr. Goldfaden visited New York some eight years ago, but finding the field occupied and being unable to earn his livelihood here, he shortly returned to Europe, where, after a long period of peregrination with travelling companies, he is said to be dying of consumption in the capital of Roumania. His early plays which form the classical literature of the Yiddish stage, have had their full share of popular success here as well as in Europe. Dramas of a better class than the average have been produced by one of the patented Jewish play writers who is by far superior to his rivals both in education and ability. But even he has been forced to succumb to the popular appetite for blood and thunder plays.

The two or three really excellent operettas which are permeated with the genuine Hebraic flavor, in their librettos as well as in their music, belong to the pen of Mr. Goldfaden, the father of the Jewish theatre. His songs touch the tenderest chord in the Jewish heart; and they are sung often to the accompaniment of sighs and tears, wherever the Yiddish tongue is spoken. Mr. Goldfaden visited New York some eight years ago, but finding the field occupied and being unable to earn his livelihood here, he shortly returned to Europe, where, after a long period of peregrination with travelling companies, he is said to be dying of consumption in the capital of Roumania. His early plays which form the classical literature of the Yiddish stage, have had their full share of popular success here as well as in Europe. Dramas of a better class than the average have been produced by one of the patented Jewish play writers who is by far superior to his rivals both in education and ability. But even he has been forced to succumb to the popular appetite for blood and thunder plays.

In addition to the regular or official authors, connected with the companies, there are several free lances whose works are sometimes bought by one of the theatres for a lump sum, ranging from $75 to $150. Royalties are almost unknown to the Jewish stage, and in the few exceptional instances where they have been paid they have varied from $5 to $10 for a performance. The average income of an author regularly associated with a theatre is estimated at from $40 to $50 a week, and one of them, at least, is said to have accumulated what in the sweatshop district is considered a snug little fortune.

There are among the Jewish actors of this city several men and women of unmistakable talent. With proper training and with the knowledge of some cultivated language, at least two of them might meet with success elsewhere. As it is their natural gifts are wasted upon all sorts of dime museum performances. Competition among the three theatres is extremely bitter, and this, so far from being conducive to improvement, has been the source of constant and progressive degeneration. It is the opinion among the better informed in the Jewish quarter that the actors could, without running the risk of losing any of the present patrons, materially extend the public from which they get their audiences by bidding for the patronage of the educated Jewish immigrants, by whom they are now shunned. Instead, they view with one another in playing upon the lowest passions and catering to the grossest tastes of the ignorant.

Improper puns and jokes are features in which the performers measure wit with the authors, for the Yiddish stage is a veritable republic, where free speech is one of the inalienable rights of each citizen, so that a Jewish actor not infrequently appears before his audience in the double capacity of impromptu author and performer. In point of fact it would be strange if he treated the playwright’s work with more respect, knowing, as he does, that is mostly a crazy quilt of plagiarisms. “Anything will do for Moses” is one of the current phrases behind the Jewish scenes, which means that the worst scribbling and the most wretched buffoonery are good enough for the uneducated Jewish playgoer. But this is disputed by many representatives of the better element, who cite cases where good plays, depicting real life of today and well acted, have met with signal success at the hands of the very “Moses.”

Strictly speaking, the Yiddish stage is Yiddish in name only. The language use on it is, in the unanimous opinion of those competent to judge, no more Yiddish than German, which some of the actors pretend it to be. The actors, with few exceptions, consider it a humiliation to their artistic dignity to use in their performances the only tongue which they and their audience know and the which they recur the moment they leave the stage; and so they treat their auditors to a species of affectedly broken Yiddish, interlarded with still worse German. However, since the characters belong to no particular race, age, or part of the world, this nondescript gibberish would seem rather suited to the plays presented.

Strictly speaking, the Yiddish stage is Yiddish in name only. The language use on it is, in the unanimous opinion of those competent to judge, no more Yiddish than German, which some of the actors pretend it to be. The actors, with few exceptions, consider it a humiliation to their artistic dignity to use in their performances the only tongue which they and their audience know and the which they recur the moment they leave the stage; and so they treat their auditors to a species of affectedly broken Yiddish, interlarded with still worse German. However, since the characters belong to no particular race, age, or part of the world, this nondescript gibberish would seem rather suited to the plays presented.

The advertisements of the Yiddish theatres on the placards and in the Yiddish newspapers are characteristic. Here are some passages.

“Overwhelming news! Read and marvel! Friday and Saturday evening, ‘Haman the Second, or the Comical Ruler.’ In preparation a celebrated drama, entitled ‘Elisheva,’ by our own author.”

“Third week! ‘Martyrdom, or the Jewish Minister’ – a great historical opera by our prominent author.”

“Goethe, the great poet, has granted us the privilege to produce his famous philosophical work, ‘Faust and Mephistopheles.’” Whether this last announcement was expected to be taken for a joke or in earnest is hard to tell. Maybe it was means for both, depending on whether the read of it happened to have an acquaintance with the name of the great Germany poet or not.

The following advertisement in one of the Yiddish newspapers is interesting.

The following advertisement in one of the Yiddish newspapers is interesting.

“ ‘Neele, or the Genius of Wilna’ – a historical opera in five acts, originally composed by Khonon Minikess; chorus and patriotic songs by William Kaiser. It is a play by the people and for the people. It is a piece of real history, and it is printed in book form to give the public an opportunity to read and study it in order that it may become popular before it is produced in some Jewish theatre.”

All the three playhouses in question give performances every evening in the week and matinees on Saturdays. Of these only the Friday and the Saturday performances are reserved by the companies, the other eves usually being farmed out by them to lodges, relief societies, or trade unions.

The theatres are furnished and decorated, and everything about them is conducted in imitation of an American playhouse, except that the relations between the members of the companies and their employees is marked by a much greater spirit of democracy. Thus the ushers, who are also the bill posters, are generally on terms of familiarity with the stars, authors, and managers. Those of the actors whose income is inadequate usually piece it out by running saloons, which are gathering places of the theatrical world of the Jewish quarter. Some time ago one of the Jewish playwrights, being out of employment, opened a beer saloon, and advertised it as a place where “art can be seen tapping lager.”

Occasionally one of the three playhouses is rented by a society of amateur performers for the production in the original of some celebrated Russian comedy or drama, and then the theatre is crowded with educated Russian Hebrews. There is a large number of these immigrants in this city, where they form a colony within a colony. Although they can all speak Yiddish, they hardly ever attend the Yiddish plays. They are, as a rule, quick to pick up the language of this country, and they gratify their aesthetic hunger by visiting the best American theatres, or by attending theatricals in the language which they know and love best in spite of the persecutions which they have undergone in the land where it belongs. ♦