From the Toronto World, May 1884

Toilers of the Night – No. 3 (Final part of a series)

Walking Against Time by the Corporation Gaslight —

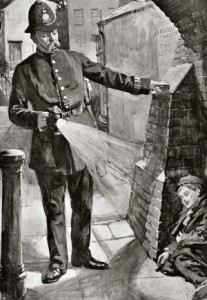

How the Sleeping Citizens are Guarded at Night

If night policemen are not exactly “toilers,” insofar as they have little manual labour to perform, they have at least “legwork” enough to render their duty by no means a light one. Even if the average constable does not cover more than twenty miles a night, he has to be on his feet all the while he is on beat. In winter he is on duty only three hours at a time, but at present he leaves the station at 8 p.m. and is not relieved until 4 a.m.

If night policemen are not exactly “toilers,” insofar as they have little manual labour to perform, they have at least “legwork” enough to render their duty by no means a light one. Even if the average constable does not cover more than twenty miles a night, he has to be on his feet all the while he is on beat. In winter he is on duty only three hours at a time, but at present he leaves the station at 8 p.m. and is not relieved until 4 a.m.

Between fifty and sixty policemen are sufficient to preserve order in Toronto during the whole night. Each of them has an allotted beat of from two to six or more blocks in length, according to the value of property and the character of the location. At some spots, as for instance at the northwest corner of Yonge and King streets, a policeman is supposed to be on the watch at all hours of the night. As a rule, there are few arrests made in the city half an hour after the closing of the saloons.

In some cases, as when a disreputable house is to be raided, the time of making arrests is purposely postponed until after midnight. When this happens a special posse is ‘told off’ for the job, the movements of which are supervised by some experienced sergeant. Such duty is not fascinating, although it sometimes has an element of excitement connected with it. And excitement is not a marked characteristic of a night policeman’s average experiences. Towing a refractory or incapable drunk to the station-house is not exactly exhilarating work, but it is at least a temporary relaxation from the monotonous tramp and occasional testings of door-handles, which go to make up the chief part of the night constable’s labour.

Take a turn along with one of these stalwart officers on king street some time after midnight, and if you are in search of a sensational arrest, choose the south (?) side of the thoroughfare. York street is as good a place for a night “policing” as can be found in the city. Yet at that particular time it is probably quiet enough. Wait a little. What was that sound? “There’s a windy gone,” remarks your companion, as the crash of broken glass falls on your ear.

The officer quickens his step to a half run and gets round the corner just as a woman’s hoarse voice makes the night hideous with cries of “Pole-eses! Pole-ces!” A few yards up the street and he is at the scene of the disturbance. It is in front of a shabby little den, an eating house below a lodging room above. On the sidewalk innumerable splinters of glass gleam in the lamp light. In the dirty little window, shaded by a dingy red curtain, a pane is missing. A slatternly, half-dressed woman, with frowsy hair, shoeless and unwashed, stands in the open door, hurling every . . . known to the York street vocabulary. A young man who stands unmoved . . . on the sidewalk. By the woman’s side is a small boy in dirty undershirt and drawers who has evidently been just awakened by the racket and crept out of his squalid bed to see the fun.

Looking beyond the figures you can see the interior of the restaurant; two little oblong tables, on which are still standing the dishes used at the last meal; a rusty stove, with a battered tin coffee pot rakishly perched on top; and walls covered with a nondescript paper, hung here and there with pictures that were probably highly colored once upon a time. From a door at the back of this luxurious banqueting hall a sleepy lodger, clad in a blue shirt and dilapidated pants, peers out with an air of mingled bewilderment and curiosity.

The policeman does not hurry himself while taking in the situation. “Ah, ye blaggard ye, it’s in the pinitinshry yees ought to be, and not stoppin’ in a dacent place at all. But here’s him that’ll fix ye for this night’s work, ye dirty mean trash, that’s fit for nothin’ but the station, an’ there ye’ll be tonight too, if I hev to walk up here an’ swear out a warrant agin’ ye.”

Now it is the policeman’s turn. He is naturally a man of few words. “What’s the trouble?” Now he knows well enough that his inquiry is only the signal for another torrent of vituperation, but, wise man that he is, he is content to wait until the virago has expended her spleen before giving his judgment of the case. So when the woman’s breath at last shows signs of failing, he manages to interject the remark, “So you charge this man with breaking your window?”

Out of another five minutes harangue he gathers the substance of the charge. The man, says the indignant historian, came home drunk and went to bed. He woke at 1 o’clock, dressed, came down stairs and asked his landlady for a quarter. She refused and he kicked the window in. The young man says it is all a lie, she only wants to get money out of him. A man who ran around the corner broke the window, merely in the exuberance of his spirits, or somebody else’s. “Guess you’d better come with me, anyway,” says the judicious policeman, and the two pace off silently towards the station.

These sorts of scenes are not altogether uncommon at nights, but they would scarcely warrant the delineation of a Toronto policeman on night duty in the character of a Vidocq or an Old Sleuth of the dime novel type. His duty is a necessary and by no means an easy one, but it is not as a rule sensational or attended by any tremendous results.