After 30 years on the force, acclaimed Toronto police inspector and detective Alf Cuddy retired in February 1912, one century ago this month, and shortly thereafter moved to Calgary, where he assumed the role of police chief. Here are a couple of stories, published in February 1912, celebrating Cuddy’s immeasurable contribution to law and order and the safety of Toronto’s streets.

* * *

‘Alf’ Cuddy, Friend Of All Who Are In Distress, But A Terror To Evildoers, As Many Criminals Testify

Among Them ‘Blinky’ Morgan — Was Ready to Tell of Young Policeman’s Earliest Capture — Fine Detective Work in Connection with the Holmes Case

From the Toronto Star Weekly, February 17, 1912

If Inspector Cuddy of Toronto goes to Calgary as its chief of police, the Western City will secure an “ideal officer.”

If Inspector Cuddy of Toronto goes to Calgary as its chief of police, the Western City will secure an “ideal officer.”

A police officer may be appreciated for his ability and bravery, but the populace hurls more bricks than bouquets. Nevertheless, Inspector Cuddy has been voted an ‘ideal police officer’ by a large majority vote in this city of Toronto. There are reasons, of course.

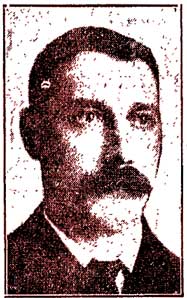

‘Alf’ Cuddy, as he is popularly called, is a pleasant looking man of 49 years, tall, not unduly bulky, quiet in appearance, but a quick thinker and a speedy mover when the occasion requires celerity.

His men say that he never considers it beneath his dignity to treat the man on the beat as a fellow-member of the force. His division has maintained the requisite discipline, however, and he has been Inspector Cuddy when any distinction has been needed.

To his constituents in Division Two, he has been a modern Solomon. When they have had domestic or other disputes, they have gone to Inspector Cuddy. Informally, but effectually, he has solved problems that might bother a magistrate on the bench.

When his brother, the late Detective John Cuddy, died, and was buried, two years ago, former prisoners attended his funeral, and were true mourners. The power of winning the confidence of everybody must be called a Cuddy peculiarity. John had it. Alf has it. So-called offenders think a lot of Alf; so do his subordinates and superiors.

The Boy From Tyrone

A tall, rather slender, moderately dark young Irishman, a native of Tyrone, joined the Toronto police force on April 19, 1882. He was 19 years old. On April 1, 1883, he was elevated from the third-class to the second-class as police constable.

A tall, rather slender, moderately dark young Irishman, a native of Tyrone, joined the Toronto police force on April 19, 1882. He was 19 years old. On April 1, 1883, he was elevated from the third-class to the second-class as police constable.

But it was not a foolish promotion. A few weeks later on York street, then in an unsavory prime, a man was shot and killed by one Blinky Morgan. It was dark, and when Cuddy learned of the crime, he chased the criminal up Pearl street, and captured him in a lane nearby.

Morgan emptied his revolver at the fleet and nervy policeman, and one piece of lead pierced the officer’s tunic, but Morgan was a prisoner. Later, Morgan killed two detectives, one in Michigan and the other in Cleveland. In Cleveland he was hanged. Cuddy was thanked by the Council, and in August, 1883, he became a constable of the first-class.

His Work as a Sleuth.

In April, 1889, Alf Cuddy was made a detective, and his cool head and excellent judgment served him well in that capacity.

The Holmes case was one of several in which Cuddy distinguished himself as a detective. Holmes murdered a man named Pitzel in Philadelphia, collected the insurance, after three of Pitzel’s children had identified their father’s body, and then killed the son and the two daughters. The girls perished in Toronto, and Cuddy found their bodies buried in a cellar.

He also did good work on the Hyams case and the Drum case.

He also did good work on the Hyams case and the Drum case.

A police inspectorship came to Cuddy in January, 1906, and now he takes Greely’s advice, and goes west, while still comparatively a young man.

Inspector Cuddy went to the Quebec Tercentenary in charge of the Toronto squad. and the present King admitted him to the Victorian Order, a proper recognition of worth and modesty.

When Inspector Cuddy completes his thirtieth year of service on April 18, he will be retired from the Toronto force on half-pay. By that time, in all probability, he will be Calgary’s chief.

Of Independent Means.

The West is likely to appeal to Cuddy. The money will not enter very largely into the proposition, because he is of independent means, and official zeal, tempered by the humanitarian instinct, has been his chief characteristic all his days.

“Calgary is the place for Cuddy,” said one of the former colleagues of the inspector, to The Star. “It’s a growing place, and his integrity, courage, and sound sense will justify Calgary’s selection. Calgary has had its eyes on Toronto police officers for some time.

“Deputy Chief Stark must stay in Toronto. He has been with us too long to leave us now, but a man after his own heart, and with many of his qualifications, is warranted in taking up this particular white man’s burden. There is not a better police officer, in Canada or out of it, than Alf. Cuddy. I know what I am talking about.”

Inspector Cuddy is an Anglican, and is a married man with two children. ♦

* * *

Reminiscences of a Police Officer, Inspector Cuddy Recalls Old Days

Some Bad Gangs Whom He Encountered in Earlier Years in Toronto

Death of Jim Maroney

The Man Who Killed Him and Shot at Cuddy Was Hanged in Cleveland

From the Toronto Star, February 24, 1912

“The first hard case I had to handle — well, I guess that would be the time I arrested Mickey Morgan in the lane behind the Palmer House in 1883, but the Kelly’s live in my mind too from a good way back,” said Inspector Cuddy, for 30 years a power of the Toronto Police Detective Department, and presently a power to be of even larger dimension in the far-away and ambitious city of Calgary, Alberta, Canada West.

“The first hard case I had to handle — well, I guess that would be the time I arrested Mickey Morgan in the lane behind the Palmer House in 1883, but the Kelly’s live in my mind too from a good way back,” said Inspector Cuddy, for 30 years a power of the Toronto Police Detective Department, and presently a power to be of even larger dimension in the far-away and ambitious city of Calgary, Alberta, Canada West.

Mr. Cuddy leaves on the tenth of next month, when his title becomes “Chief of Police.” The inspector was a lad only when he joined the Toronto force in 1882. Born in Tyrone, Ireland, where so many good men come from, his parents sought fortune in Canada, and in due time Alf, like to many other north of Ireland men, joined the Toronto police force.

North of Bloor street was all open country or bush land then. The city limits stopped at the Don, and so did the city police. County constables did duty across the river. Later there was a period when the section south of Queen street came into the city and under city police supervision for a certain distance east. Queen street was the dividing line, and the north half of the street was in the county, while the south half was in the city.

The situation was a difficult one, sometimes. Talking about the fights that used to occur between the River street gang as representing the city and the gang from over the Don, the Inspector made his sad reflection on the Kelly’s.

Sackville Street Gang.

“A harder gang than that of River street, or any of them in my time,” said the Inspector, “was the Sackville street gang, which means the Kellys. There were two families of the Kellys. For roughness they couldn’t be beaten to-day, or in the early days either, when Toronto had rougher characters and the police had a rougher time of it by far than they have now. There were no patrol wagons then. A constable had to bring his man all the way to the station. I’ve known one man to make twelve arrests in one night. York was the toughest street in those days. Lombard was pretty bad. The toughs used to elect a mayor over there. Dandy Mann was the first mayor of Lombard street, Jerry Sheahan was the second after Mann died.”

Nosey Kelly, of Sackville street, which was fairly tough at that time too, was a great man for fighting the police. He got into a highway robbery zone of suspicion, unfortunately however, and moved to scene of his activities to Cleveland, where he remained for twenty years. Then, overcome with thoughts of home and dear old Sackville street, he came back to Toronto and reappeared in his boyhood haunts. But there was still a warrant out for him, and the north of Ireland arm of British law is long, and the north of Ireland memory likewise. Detective Cuddy appeared at Tim Sheahan’s place on Ontario street one morning at four. Tim was a friend of Kelly’s. Cuddy, who had an “inkling,” placed a man at the back door and one at each window. Time drove a coal cart for Elias Rogers in the day time. He entertained at night, it was sometimes said, without a license. Tim came to the door.

Witnesses All Dead.

“I was just going to be giving you a tip,” said he confidently when he saw who was there. “He’s not here — the man you want. He’s away beyond up at Fiddler’s. Fiddler’s place was close by his brother Nosey’s old house, away over on Sackville street.

“I’ll just take a little look around your place first,” said Inspector Cuddy in no wise cast down.

“Oh, well, in that case, I might just as well be telling you the truth,” returned Tim soothingly. “He’s here sure enough. Come in, take him, there’ll be never a word said.”

Mr. Cuddy did so, and Nosey came along like a lamb. But they had to let him go. The charge of highway robbery still held good, but twenty years had passed. The parties were dead.

“How about Mickey Morgan in the lane behind the Palmer Hotel back in 1883?” asked The Star.

“Well, that was my first hard tussle,” replied the Inspector modestly. “I was only a lad you might say at that time, just out of my first year on the force. I joined on April 19, 1882. I took Mickey Morgan after he shot Jim Marony at the corner of Pearl and York streets on August 7, 1883, at 11 o’clock at night. He ran up the lane behind the Palmer House. When I followed him he shot at me. The bullet went through my coat and through my trouser pocket. An inch closer and he’d have had me in the groin. He made a hole through one lining of the pocket and not the other. He fired again just as we clinched, but I got hold of his arm and the bullet went between my feet into the ground. I was stronger than he was and I took the revolver away from him. Then he quit. ‘Don’t hit me,’ he said. There was no need to hit him. I took him to the station. Then Charley Bell came up from King Street, and the two of us took him along. When I came back they were carrying poor Maroney to his own home on Pearl street. He was stone dead . . . .”

(Morgan was sentenced to prison but escaped after eighteen months, the story continued.) He and a gentleman named Kennedy were put in charge of a coal chute at the prison. They went down the chute, and burrowing under the coal, dug their way under the foundations, covering up the hole with coal each night, and appearing finally at the surface outside.

Shot an Officer.

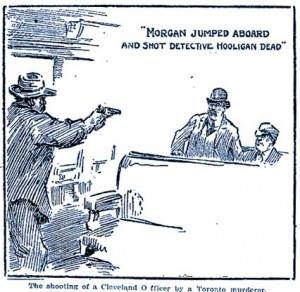

Morgan’s specialty was robbing fur stores. Some time after his escape, his friend Kennedy was arrested in Cleveland for fur robbery. He was in a train being taken to trial, when at a stopping place Morgan jumped aboard and shot Detective Hooligan dead, and Kennedy and himself escaped.

Mickey Morgan turned up next in Michigan. Sheriff Lynch heard that he was at a certain disreputable house in his town. He went down there. He saw Morgan sitting on the verandah clad in a smoking jacket, with his hands in the side pockets. Mickey also saw Lynch, who was in uniform. When he approached, Morgan pointed a gun through the pocket of his smoking coat and shot Lynch, who died three days afterwards.

He grappled Morgan on the verandah first, however, and fought for a long while with him. His strength was beginning to fail when a butcher’s boy of seventeen or eighteen years came along, took in the situation, and joined in. He succeeded in getting the revolver. Another boy came along, and they held the murderer down till the police came. As there was a law against capital punishment in Michigan, Morgan was taken back to Cleveland in Ohio and tried for the murder of Hooligan, for which in the due of the American courts, he was safely hanged. ♦

Read about the Holmes-Pitzel murder case, as told in The Devil in the White City, here.

Read about an infamous murder case in Victorian Toronto here.