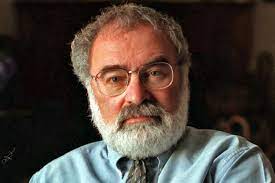

Irving Abella, the author and former history professor who died on July 3, 2022 at age 82, wore many hats throughout his distinguished career. He was chair of Canadian Studies, the Shiff Professor of Canadian Jewish History, chair of Canadian Professors for Peace in the Middle East, chair of Canadian Jewish Archives, Governor of York University, editor of Middle East Focus, chair of the Governor General’s Literary Awards for Non-Fiction, president of the Canadian Historical Society, president of the Academy of the Arts and Humanities of the Royal Society of Canada, and president of the Canadian Jewish Congress. His books include A Coat of Many Colours: A history of Canadian Jewry, and (co-author) None Is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933-1948. He was the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, the National Book Award, The Order of Ontario, The Order of Canada, and several honourary degrees. This article, which he wrote some 50 years ago, appeared in The Canadian Jewish News of April 7, 1972.

A witty, immodest biography: Review of So Far, by Meyer Weisgal

by Irving Abella

Reading Meyer Weisgal’s autobiography So Far is like reading a history of the Zionist movement in the past 50 years. Weisgal, the founder and long-time president of the Weizmann Institute of Science, seems to have been in on most of the decisions affecting Zionism and the creation of the State of Israel in the years between 1920 and 1948. Not only was he privy to these decisions, but according to no less an authority than Weisgal, some of the more important ones he made himself.

Reading Meyer Weisgal’s autobiography So Far is like reading a history of the Zionist movement in the past 50 years. Weisgal, the founder and long-time president of the Weizmann Institute of Science, seems to have been in on most of the decisions affecting Zionism and the creation of the State of Israel in the years between 1920 and 1948. Not only was he privy to these decisions, but according to no less an authority than Weisgal, some of the more important ones he made himself.

A list of Weisgal’s friends reads like a Who’s Who of Jewish life over the past two generations. He seems to have known everyone, and has stories about them all. His cronies include such dissimilar characters as Albert Einstein and Otto Preminger, Levi Eshkol and the embittered anti-Zionist columnist Dorothy Thompson, the pompous, assimilated German-Jewish director Max Reinhardt and the militant “Yiddishist” Shmaryahu Levin.

Above all, it was his curious relationship with Chaim Weizmann that made Weisgal so important to the Zionist cause. Why the urban, sophisticated Weizmann chose as his advisor and representative in America this unpolished, outspoken Polish immigrant, is something not even Weisgal can satisfactorily explain. Yet it is as Weizmann’s agent that Weisgal makes his great contribution to the Zionist movement.

Weisgal is a man of many talents – journalist, theatrical producer, polemicist, fundraiser, raconteur – all of which he fully documents in this book. Like its author this autobiography is colorful, witty, opinionated, warm and immodest.

Of the great issues of our times, Weisgal always seems to have been on the right side, or so he would have us believe. Whenever in doubt he gives himself the benefit. His hates are as passionate as his loves. His admiration of Weizmann, Moshe Sharett, Levi Eshkol, Lord Sieff and Louis Lipsky is as fulsome as his dislike of Mrs Weizmann, Ben Gurion, Jabotinsky, and Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver, amongst others.

The story Weisgal tells in this book is inspiring. It is the tale of a young immigrant from one of those countless tiny Polish towns whose name is unpronounceable and from which all our parents or grandparents seem to have originated, who comes to America at the turn of the century to seek his fortune.

Within a short time, through a series of fascinating and intriguing incidents, he becomes a power in the Jewish community, and a charter member of the Zionist establishment. Though this is an intensely personal book, it abounds with incisive character sketches of most of the Zionist leaders of this century.

Although the book seems comprehensive, for Torontonians at least, there is one significant omission. Of the 400 pages in the book, Weisgal devotes only one to his two-year residence in Toronto. This hardly does justice to his impact on Jewish life in this city.

Weisgal spent two years in Toronto in the early 1930s, countering Holy Blossom Rabbi Maurice Eisendrath’s poisonous anti-Zionism

In 1929 Holy Blossom Temple on Bond Street acquired a new rabbi, Maurice Eisendrath. Immediately, Rabbi Eisendrath shocked some of his congregation and many in the Toronto Jewish community with his vituperative attacks on Zionism from his pulpit and from the pages of the Jewish Review. At the invitation of one of Eisendrath’s shaken congregants, the saintly Rose Dunkelman, Weisgal came north to counter the rabbi’s anti-Zionist poison.

Once in Toronto, Weisgal founded the Jewish Standard as an antidote both to Eisendrath’s fulminations and to the increasingly violent assaults on the Zionist establishment from the vocal Revisionist organization in this city. He spent much of his time here debating Eisendrath and the Revisionists, and when he left Toronto, the Jewish Standard was flourishing, as it continued to do for many years, and Rabbi Eisendrath had begun his swing into the Zionist camp from which he never again strayed.

Quite clearly, Weisgal is one of the major figures in the history of 20th century Jewish life, not only in the United States and Israel, but in Canada as well. The secret of Weisgal’s success is obviously his cockiness, his exuberance, his charm, his “joie de vivre” and naturally, his chutzpah. After all, what other 80 year old man would entitle his autobiography . . . “So Far” ? ♦