From the Brisbane Courier Mail, May 26, 1934

CANADA is to be numbered among the new countries, yet it enters in July upon the 400th year of its history.

CANADA is to be numbered among the new countries, yet it enters in July upon the 400th year of its history.

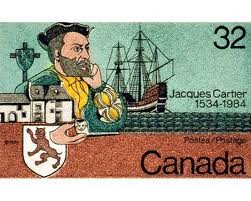

On July 24, 1534, Jacques Cartier, mariner of St. Malo, in Brittany, set up a cross on the mainland of Canada at Gaspe, and took possession of the land in the name of the King of France. This quater-centenary and the centenary of the incorporation of Toronto are to be celebrated in Canada in elaborate pageantry, with the co operation of Great Britain and France, the two parent nations.

Toronto, which was 100 years ago a small town of 10,000 people, known as Muddy York, and is now a great commercial and tourist centre of 850,000 population, has set aside three three-day periods for prolonged festivities.

The Cartier commemorations (writes a correspondent of the London Daily Telegraph) are to be very costly and impressive. A cathedral is already in the making on the spot where Cartier set up his 30 ft. cross, and he and his men knelt and made signs to the Red Indians, looking and pointing towards heaven, that by means of the cross they had redemption— to the “admyration” of the natives.

FRANCE TAKING PART.

On the initiative of Senator Rodolphe Lemieux, brother of Mr. L. J. Lemieux, the Agent-General for Quebec in London, the Canadian Government is giving 300,000 dollars towards the celebration, Quebec Province 100,000 dollars, and other provinces and cities large amounts. France will send a deputation by a special ship, possibly with a naval escort, and a painting of the landing of Cartier, ordered by President Doumer shortly before his assassination, is to be presented to the new cathedral.

Gold and the Faith were the guiding stars of Cartier’s expeditions. He was 43 or 44 when his Most Christian Majesty Francis I authorized him to go in search of some of the precious metals and gems of the New World which were so enriching the kings Most Catholic enemy, Charles of Spain.

Gold and the Faith were the guiding stars of Cartier’s expeditions. He was 43 or 44 when his Most Christian Majesty Francis I authorized him to go in search of some of the precious metals and gems of the New World which were so enriching the kings Most Catholic enemy, Charles of Spain.

In two vessels of about 60 tons each Jacques Cartier set out on April 20, 1534, with 60 companions. He is portrayed as a lean, dark man, with strong features, a harsh, beaked nose, and black, dominant eyes. With his personal ambition and his dry sense of humour, he was not the ideal evangelist. While he never failed to set up crosses, even on the barren coast islands of Labrador — which he considered must be the land given by God to Cain— the researches of Mr H. P. Biggar, the Canadian archivist in Europe, indicate that he never lost sight of economic possibilities.

CANADA’S GREAT AUKS.

These at first sight seemed slight. The Newfoundland fisheries were already known, and had been known since Cabot in 1497 caught cod merely by lowering baskets into the sea — possibly even before. The natives appeared to be the poorest people in the world, and would literally strip themselves naked for the metal tools and ornaments the French were prepared to barter. In the grey and forbidding Gulf of St. Lawrence, where icebergs drift from the north, there were also, fisher men said, supernatural terrors.

Griffins inhabited Labrador, alarming bears “white as an egg” swam in the sea, and two islands were infested with demons, all crying together. These imps were agreeable to look at, but extremely malicious. Food was scarce, except for Great Auks, which Cartier’s men pickled in large quantities, thereby contributing their share to the extinction of those hapless, penguin-like creatures.

Griffins inhabited Labrador, alarming bears “white as an egg” swam in the sea, and two islands were infested with demons, all crying together. These imps were agreeable to look at, but extremely malicious. Food was scarce, except for Great Auks, which Cartier’s men pickled in large quantities, thereby contributing their share to the extinction of those hapless, penguin-like creatures.

Cartier’s first voyage was a disappointment. He found no gold, no passage to Cathay, and he converted no natives, for they could not understand when he read the Gospel to them. On this second voyage, a year later, Cartier followed the St. Lawrence River to Stadacona and Hochelaga— Quebec and Montreal— and found a smiling land flowering in a radiant sun. He then wintered at Quebec, and discovered that the rigours of the climate were not too great for the endurance of Europeans. From this expedition dates the name Canada— in reality it is the Huron-Iroquols word for village— and the news of the mysterious kingdom of Saguenay, “rich in gold, rubles, and precious stones.”

LAND OF ONE-LEGGED.

Donnaconna, the chieftain of Quebec, whom he took back to France, told tales of the wonders of the New World which inflamed the cupidity of the Court and excited the laughter of Rabelais.

There were lands, he said, where men wore woollen clothes and had an abundance of gold and copper, lands of pigmies and “men who fly,” lands whose inhabitants never ate nor digested, and others where men had only one leg. Poor Donnaconna did not long survive the telling of these tales. Although he had been baptized and excellent care was taken of his soul, his physique was unequal to the strain of European civilization, and he died within a year or two, to the great detriment of the next expedition— in 1541.

Cartier, under the impression that he had at last found treasure, slipped away to France with a cargo of iron pyrites and worthless crystals, which he took to be gold and jewels. This exploit enriched only the French language, which gained a new expression for the meretricious— “Voila un diamant de Canada.” With this contemptuous phrase closes the prelude to the story of French Canada.

For more than half a century the wars of religion occupied France, and fishermen and a few fur traders alone braved the North Atlantic crossing. But Cartier had shown the way. He was the discoverer, the first explorer, the first pioneer, the first historian of Canada. It is not recorded that he willingly caused harm to any one. His courage and ability were harnessed to tremendous aims, and his is the first of the great names of New France— Champlain, La Salle, Frontenac, Montcalm — which are the imperishable echoes of high adventure.

Toronto is another Indian word, meaning “place of meeting”: the site is one where trails and water routes converge. It first appears in recorded history as a centre of trade in 1750, when the French built a fort and small trading settlements under the name of Fort Rouille. In 1793 it be came the capital of Upper Canada, and was called York in honour of the Duke of York, son of George III. Three years after its incorporation it became, in 1837, the centre of the rebellion in Upper Canada.

Toronto is another Indian word, meaning “place of meeting”: the site is one where trails and water routes converge. It first appears in recorded history as a centre of trade in 1750, when the French built a fort and small trading settlements under the name of Fort Rouille. In 1793 it be came the capital of Upper Canada, and was called York in honour of the Duke of York, son of George III. Three years after its incorporation it became, in 1837, the centre of the rebellion in Upper Canada.

TORONTO TO-DAY.

From Lake Ontario, Toronto shows a skyline reminiscent of New York, with docks and skyscrapers. The city stretches for miles behind, with many parks and trees everywhere, so gorgeously coloured in the fall of the year that one would think them on fire. Toronto claims to be the best lighted city in America, to possess the tallest office buildings in the British Empire, the largest department store, and the largest heated swimming-pool in the world, and to provide the cheapest electric light and power any where. It is, too, in summer time a huge holiday resort. ♦