Born about 1620 in Ostrog, Volynia, Rabbi Nathan Hanover and his family were among the countless Jews in Ukraine and eastern Poland whose lives were disrupted by the Chmielnicki massacres of 1648 and the intermittent attacks that continued for years afterwards.

Born about 1620 in Ostrog, Volynia, Rabbi Nathan Hanover and his family were among the countless Jews in Ukraine and eastern Poland whose lives were disrupted by the Chmielnicki massacres of 1648 and the intermittent attacks that continued for years afterwards.

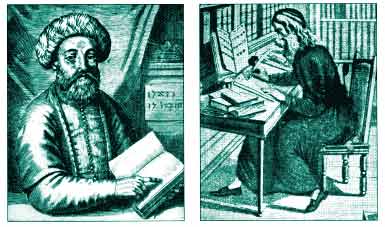

Hanover travelled extensively over the region of devastation, speaking with many affected people and recording their stories. Author of several books, his most famous by far is Yeven Metzulah (“The Abyss of Despair”), a graphic and gripping account of the horrors that occurred in Ukraine and eastern Poland when Bogdan Chmielnicki led the Cossacks into attack.

Historians regard the Chmielnicki massacres as a precursor to the Holocaust, and Yeven Metzulah as a precursor to the dark genre of books, known as yizkor buchim (remembrance books), that chronicle the destruction of various pogroms and the Holocaust.

So popular did Yeven Metzulah become, according to historian William Helmreich, that in some communities of Eastern Europe it was customary to read it annually during the traditional “three weeks” in summer, and new editions often appeared after each new wave of persecution — right up until the Ukrainian pogroms that occurred during and following WWI.

One of the classic texts of Jewish martyrology, The Abyss of Despair focuses on the nightmarish wave of anti-semitic violence that resulted when Tatars from the Caucaucus region joined the Ukrainians in their nationalistic rebellion against the Polish nobility and their largely Jewish landlords. Tens of thousands of Jews — by some estimates as many as 100,000 Jews — were slaughtered. Although Hanover’s numbers are not reliable and he embellished his testimonial with poetic descriptions and Biblical allusions, his book stands as the most enduring memorial to the destroyed communities he describes.

He was living in his wife’s town of Zaslaw, one of the first places to be hit; he and his family fled but most of the town’s Jews, including his father-in-law, were killed. While on the run, Hanover learned that his own father had also been killed in a Cossack raid on Ostrog. A gifted orator, Hanover supported his family as an itinerant preacher. Wandering through eastern Poland and Ukraine, he spoke with refugees from many ravished communities and heard many horrific stories.

In Ostropol, Rabbi Samson exhorted the community to repent of their sins so the town would be spared from attack; the community followed his advice but “the evil decree had already been sealed.” In Polannoe, thousands perished like lambs without fighting back: “A single Ukrainian invading a dwelling which housed several hundred Jewish persons would kill all of them and would meet no resistance.”

Hanover’s pen recorded individual atrocities on a par with anything the Nazis would later devise. It also relates many tales of Jewish heroism in the face of unspeakable cruelty.

In Tulczyn, the Ukrainians assembled the Jews in an enclosed garden, where several rabbis exhorted the community not to abandon their faith despite the threat of death. “Three times the Cossacks told the Jews, ‘Whoever wishes to change his faith and remain alive, let him sit under this banner.’ Not one Jew moved. Eventually, the Cossacks attacked and approximately 1,500 souls perished by all sorts of terrible deaths.”

In some towns, women escaped certain rape by jumping into moats surrounding the fortress-walls; many drowned or were stabbed in the water. Hanover tells of a beautiful maiden from a wealthy family whom a Cossack forced to become his wife.

“But before they lived together she told him with cunning that she possessed a certain magic and that no weapon could harm her. ‘If you do not believe me, just test me,’ she said. ‘Shoot at me with a gun, and you will see that I will not be harmed.’ The Cossack, her husband, in his simplicity, thought she was telling the truth. He shot at her with his gun and she fell and died for the sanctification of the Name, to avoid being defiled by him, may God avenge her blood.”

As the invaders besieged one Jewish village after another (more than 700 in total), the villagers fled. “Whoever had a horse and cart travelled in it. Those who did not possess a horse and cart, even though they had sufficient money to buy them, would not wait, but took wife and children by the hand and fled on foot, casting away all belongings.”

Hanover describes roads clogged with horses and carts and refugees on foot, the air charged with wild rumors and panic. “Everyone threw from his cart silver and gold, vessels, books, pillows and bed covers in order to be able to escape more quickly, to save the lives of his family. The field was cluttered with gold, silver and clothes, and no Jew paused to take them.”

For centuries before the Chmielnicki massacres, Jews had been moving eastward across Europe from Spain, Alsace and the Rhineland into Poland and Turkey. After 1648, the eastward trend was reversed. Many historians have suggested that the abyss of despair into which the Jews fell after 1648 set the stage for the emergence of the false messiah Shabbetai Tsvi about 1666, and for the revolutionary Hasidic movement of the next century.

“The brutality of Chmielnicki made the work of the Nazis that much easier,” Helmreich observes. “As we read Hanover’s description of the atrocities committed by Chmielnicki and his hordes, it becomes clear that Hitler’s torture chambers were only technological refinement — the precedent had already been set.” ♦

Yeven Metzulah: The Abyss of Despair, by Nathan Hanover. Translated by Abraham Mesch. Transaction Books (1983).

Yeven Metzulah: The Abyss of Despair, by Nathan Hanover. Translated by Abraham Mesch. Transaction Books (1983).

© 2005